Thought Leadership

Can new Serie A investors wake football’s sleeping giant?

16 MIN READ

Thought Leadership

Inspired by what you’re reading? Why not subscribe for regular insights delivered straight to your inbox.

Of all the existing speculation around football investment, private equity interest in Serie A’s TV rights is perhaps the most eye-catching. There are as many as seven firms interested in investing in the league, with reported bids valuing the league at a little over £10bn (€11bn/13bn).

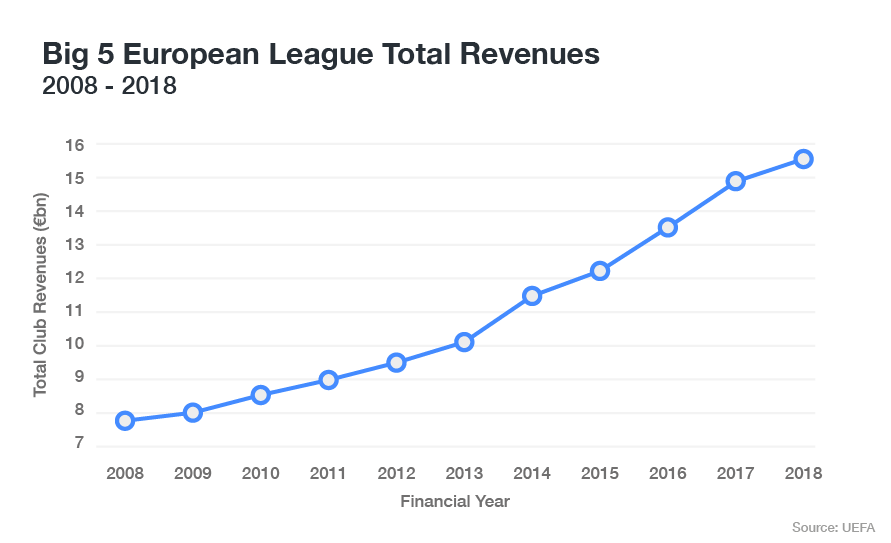

Sports investment has always been attractive to those who can afford it, as much for the kudos as for the uncertain capital returns. More recently, however, sports investment, and particularly football investment, is recognised as a bona fide opportunity to make money. Growth in revenue from media and commercial rights has diversified club business models, while new technology, social media platforms, gaming, betting, and eSports are presenting the industry with new ways to interact with fans and monetise their interest.

While football investment has historically focused on clubs, in other sports there has been notable growth in investments in rights-holders themselves – CVC Capital Partners’ investment in Premiership Rugby and Liberty’s investment in Formula 1 being notable examples. Football is now catching up through the interest in Serie A and Bridgepoint’s recent interest in the Women’s Super League. This approach makes sense for investors interested in capitalising on the attractive dynamics of a growing market, while also managing their risk.

Clubs are exposed to the vagaries of on-field performance, which can be hard to control. Football is a low-scoring sport where success is not always bestowed on the most-deserving teams – our models suggest that the better-performing team on the day wins only two thirds of the time, making results inherently volatile. Such volatility is unattractive to investors seeking to limit risk, especially where something as material as relegation can undermine a club’s ability to benefit from the market dynamics that attracted them in the first place.

Club success is also largely determined by the league that you’re in – perhaps the only reason why AFC Ajax aren’t consistently the European force of old is because they happen to compete in the Dutch Eredivisie, where they receive less than 10 per cent in media rights revenue than AFC Bournemouth did in the Premier League.

Where clubs need to win each week, leagues simply need to put on a show, regardless of who ends up as champion. Leicester City’s unexpected triumph in the 2015-16 season was just as valuable to the Premier League as Manchester City’s title in 2017-18, despite not being one of the global brands in the competition. The narrative of the Manchester club’s sustained excellence in reaching 100 points is no more compelling than Leicester’s extraordinary defiance of the odds.

One risk that leagues face, outside of the current Covid-19 crisis, is the change to the broadcast market through the long-anticipated shift from linear to OTT platforms. But this may not be sufficient to deter investors who can probably make a reasonable bet that there will always be buyers for quality content from the world’s most popular sport.

Similarly, the omnipresent concept of the European Super League remains a threat to Europe’s ‘Big 5’, although the barriers to its implementation are significant enough to allay much of the nervousness that this possibility inspires.

The Golden Era

The success of the Premier League in growing its broadcast rights has shown what is possible when the product both captures the imagination of a global audience and is sold effectively. The Premier League’s financial dominance of World football is absolute, with its broadcast deals worth nearly double that of LaLiga’s, which is in second place.

But memories are short, and it’s easy to forget that the Premier League was founded less than 30 years ago, against a backdrop of hooliganism, Heysel and hopeless facilities, in an attempt to keep up with the then-giant of world football – Serie A. The Italian top flight was arguably even more dominant then than the Premier League is now.

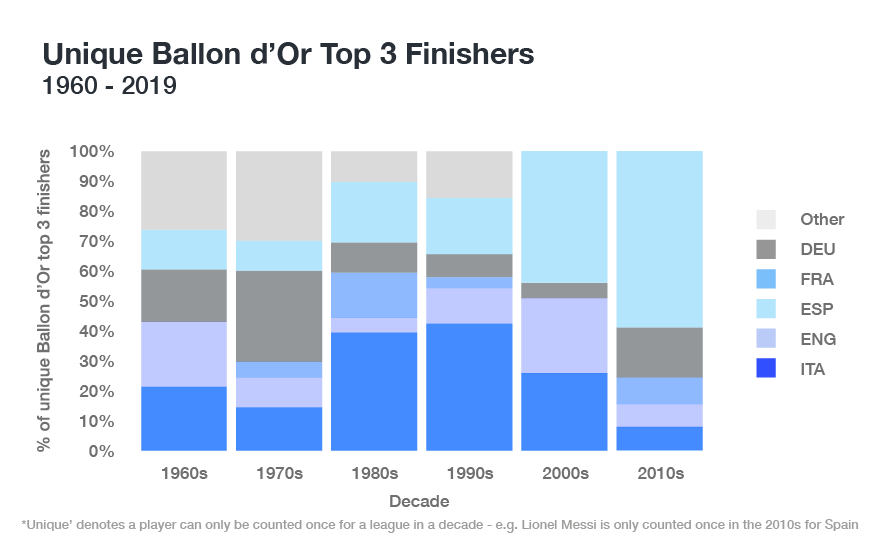

In the 80s and 90s, 13 of the 20 Ballon d’Or winners played for Italian teams. And this wasn’t down to one or two once-in-a-generation players – the awards are spread among 8 different players playing for three different clubs, none of whom are Diego Maradona who, despite being probably the greatest player of his generation, was ineligible for the award during his seven years at Napoli between 1984 and 1991 for being South American.

Serie A was home to football’s all-time greats during this period – Platini, Klinsmann, van Basten, Maradona, Gullit, Mancini, Hagi, Vialli, Bastitua, Baggio, Weah, Del Piero, and the original Ronaldo to name a few.

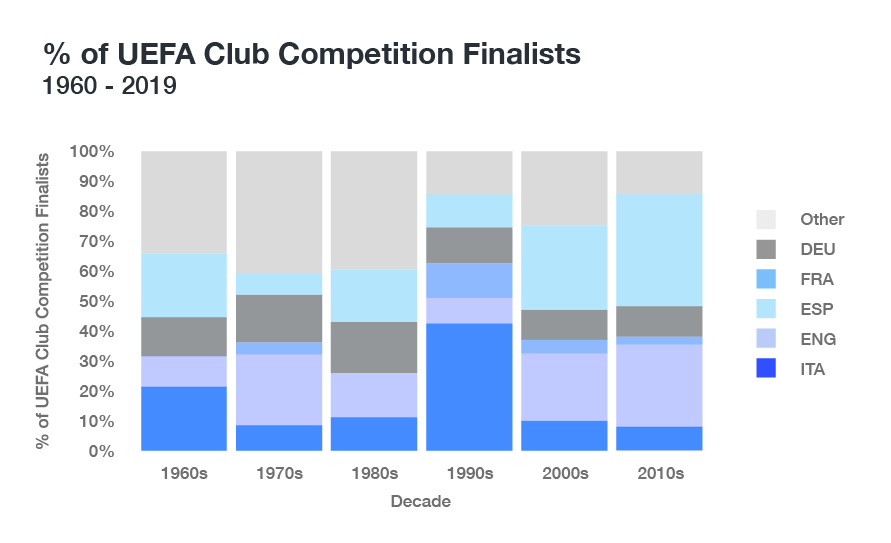

It was not just the players in Serie A taking the plaudits. Italian teams were also dominant in European Football. Pick any random European or Uefa Cup final to watch between 1989 and 1998 and you have 55-per-cent chance of seeing an Italian team. Serie A was also highly competitive domestically – during the same period there were five different domestic champions.

Dominance on the field was matched by financial dominance off it – by the summer of 1998 nearly half of the 100 most expensive deals in history involved an Italian buyer.

During the 80s and 90s, Italian clubs were the best and the richest So what happened?

Decline & fall

There are myriad reasons behind the decline of Serie A to being one of today’s ‘also-rans’ among the big five – corruption, crumbling infrastructure and a footballing culture tarnished by ‘ultras’ among them. But it was ultimately the timing of significant events from 2006 that created a storm that Serie A was unable to weather.

The damaging sequence of the Calciopoli scandal (where several Italian clubs were found to be influencing the selection of referees in their favour), the financial crisis, the introduction of Financial Fair Play (FFP), and a challenging broadcast environment served to bring an end to any hopes the league may have had of keeping pace with the growth of the Premier League and Spain’s biggest clubs.

There is a strong correlation between a country’s wealth and its football revenues, and the financial crash had a disproportionate impact on the Italian economy. Italy had the second highest debt to GDP ratio among EU countries at 120 per cent, meaning when the crisis hit and the cost of debt spiralled, Italy had to take on significantly higher repayments at a time when they could ill-afford it. Further borrowing was required to service the debt at ever less attractive rates, creating a vicious cycle and consigning Italy to a longer period of recovery compared to many of its European counterparts.

While the crisis hit Italy harder than most, the specific context of Serie A’s most famous clubs also made them more susceptible to the aftershock. The financial muscle of Milan and Internazionale was founded on the financial commitment of owners whose business interests suffered, curbing their appetite to lavishly fund their clubs.

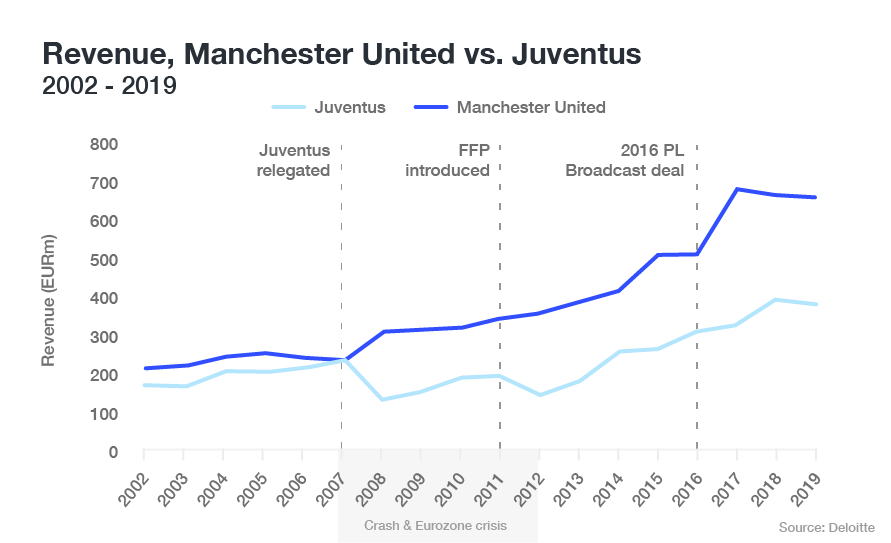

Juventus – being listed and therefore more professionally run – was also vulnerable but for different reasons. The Old Lady had spent the 2006-07 season in Serie B, having been relegated in the wake of the Calciopoli scandal. In the time required to rebuild both their league position and their reputation, the club lost ground to major European rivals – a revenue gap that they have since failed to close in part due to the wider economic headwinds facing Italy at the time.

Juventus were not the only iconic team to suffer. The scandal also implicated Milan, Lazio, and Fiorentina, and served to bolster the prevailing, damaging notion that Italian football – and Serie A – was habitually corrupt.

With less money floating around the economy for a prolonged period of time, and still reeling from their self-inflicted wound, Italian clubs struggled to recover fast enough to compete with the riches lavished on elite players and coaches by Europe’s other footballing super powers – principally Real Madrid, Barcelona, Bayern Munich and Manchester United, as well as the nouveau riche Premier League Clubs.

The subsequent exodus of Serie A’s finest did lasting damage to the competition’s commercial and broadcast value, sabotaging its ability to keep pace with the Premier League’s rise.

With Italian clubs having fallen behind in revenue terms, the timing of Financial Fair Play (FFP) then provided a moat for clubs that had managed to grow their revenues prior to its implementation in 2011. FFP raised the drawbridge on the option for Italian clubs to buy their way back to the top, forcing Serie A to reconcile their sense of entitlement to compete among Europe’s elite with their own grim financial reality.

It’s telling that Qatar, Abu Dhabi, and Roman Abramovich all created so-called ‘super clubs’ outside of Italy prior to FFP’s implementation, and we haven’t seen it done since. FPP ultimately ensured that Serie A paid a heavy price for the failure of the global economic system and its own susceptibility to villainy.

As well as these wider market issues, Italian clubs have also had to battle to grow specific revenue streams.

Where broadcast revenues have driven much of the Premier League’s growth, Italian football has faced a more challenging broadcast environment. Serie A has failed to replicate the rivalry between Sky and BT Sport that has driven much of the growth in the Premier League’s domestic rights.

The Melandri Law has also played a part in limiting international growth – through restricting rights cycles to three years it has effectively removed any incentive for international broadcast partners to invest in building an audience. The Premier League’s broadcast rights attract nearly three times more partners than Serie A.

The stadium infrastructure of Serie A clubs also limits their ability to generate matchday income. While the likes of Roma’s and Fiorentina’s stadium projects have spent years in a bureaucratic morass, Tottenham Hotspur have built and opened a new home regarded by many to be the finest in the world.

In contrast, few of the stadiums in Serie A are privately-owned, and most are creaking structures, offering a dated matchday experience and limited capacity for corporate hospitality. While the likes of Tottenham can look forward to significant matchday revenues once social distancing is eased, many Italian teams are struggling to break the glass ceiling imposed by their crumbling facilities.

The 2007 Deloitte Money League ranked Juventus as the third-wealthiest team in the world, behind the giants of Spanish football Real Madrid and Barcelona, but ahead of all English teams. That there are now six Premier League teams ranked higher than the wealthiest Italian team (Juventus in 10th) serves to illustrate Serie A’s struggles in the years since Calciopoli broke.

Why now?

It is no coincidence that the investment opportunity has brought several parties to the table.

Italian football has too much going for it to be in terminal decline and there is a strong case that Serie A may now be close to its nadir meaning that, with an effective strategy, the only way is up.

Italy remains among Europe’s biggest economies and most lucrative football markets, meaning league and club revenues remain considerable, relative to most other European leagues.

There is also significant, latent value in the Serie A brand. History matters, and the record of Italian teams in prestigious European competitions is enviable – teams from Serie A have featured in more European Cup finals than all other leagues barring LaLiga (just one fewer). Serie A also has a high number of different winners (second again, this time behind the English top flight) – historic success has created a number of the big-branded teams required to make a compelling domestic football competition.

There is also a practical reason for the timing. The current broadcast deal expires at the end of the 2020-21 season, creating urgency in ensuring that there is sufficient time to affect the auction for the next rights cycle. The impact of Covid-19 on club finances has served to further increase the desire for haste.

A strategy for success

While the raw materials are there, a compelling strategy is required to make something of them. In a competitive tender process – which the Serie A investment clearly is – aside from the size of the cheque, the investors with the most compelling plan will stand out.

To that end, at 21st Club we have developed ‘Football’s Flywheel’ to provide some structure to these strategic conversations. The framework aims to capture the key elements of making a long-term success of any league and to highlight the interplay between the footballing and commercial elements of league strategy.

The simple idea is that success breeds success – finding a way to increase the number of fans grows the value of the competition, which results in greater revenue from broadcast and commercial sales. When this revenue is distributed to clubs, you see greater investment in talent resulting in better football and a more compelling competition, bringing more fans to the table, and so on.

The logic is simple, but it can be hard to get the wheel turning. Like unscrewing a rusty bolt, you need good initial purchase and significant effort to wrest it from its position before it begins to turn with ease. The Premier League’s initial purchase derived from its singular focus on maximising broadcast yield, while at the same time accommodating the rise of clubs like Chelsea and Manchester City to increase the overall competitiveness (and therefore watchability) of the league. Serie A will have to define what will provide their initial purchase.

Turning the wheel for Serie A

There has already been much sensible discussion around selling Serie A’s broadcast rights more effectively and funding stadium development across the league, but there are also plenty of performance-related levers that a smart investor can pull that will help serve the same ultimate purpose – greater broadcast revenue.

A key underlying principle of the flywheel is the influence the quality of the football has on rights values. Too often, growth strategies ignore the critical role that clubs play in in the ecosystem, with leagues preferring to leave their clubs to their own devices. But where clubs can be encouraged to grow revenue more effectively and invest their resources in talent more efficiently, the league will ultimately benefit from a better, more valuable product – i.e. more entertaining football matches.

Finding ways to support clubs in investing more in talent that serves both the purposes of the clubs and the league would be a good start. According to our research about the efficiency of teams at turning resources into results, Serie A clubs are among the most wasteful of the big five. Addressing this will be both necessary and difficult, but there are successful case studies where clubs and leagues work together in service of their shared interests.

The Canadian Premier League, for example, has partnered with 21st Club to provide its clubs with a technical scouting system both to identify undervalued talent from the global recruitment market, but also drive cost efficiencies through centralisation. While this exact approach is unlikely to fly in Serie A, the general principle of centrally procuring resources at preferential rates makes sense. It provides clubs with the tools necessary to make sound strategic and recruitment decisions, while also saving on cost.

It is this principle that underpins the Premier League’s Football DataCo, an entity designed in part to provide access to market-leading data and technology services to Premier League clubs. And it is not solely to serve player recruitment needs. Much of the products and services procured are to aid clubs in driving fan engagement and growing their fanbase – another key component in the flywheel, and a prerequisite to growth in the value of commercial and broadcast rights.

The turning of the tide may already be in evidence. Over the last four years, Serie A has accounted for 18 per cent of the best players across the Big 5 leagues according to our model, up from 13 per cent in the preceding four-year period (leapfrogging the Bundesliga).

Some of the world’s most famous (and expensive) players now call Italy home – Christian Eriksen, Romelu Lukaku, Cristiano Ronaldo, Diego Godin, Alexis Sanchez, and Zlatan Ibrahimovic, for example, have all recently moved to Serie A – signs that the financial muscle may be returning.

In particular, Ronaldo’s move to Juventus has given the club new impetus to grow their commercial revenue, with the player’s social following opening up the club to new markets in Asia and the Americas. Matthijs de Ligt is also one of the hottest young properties in world football, and his choice of Turin over Madrid or Barcelona bodes well for the league.

Likewise, Internazionale’s purchase of Lukaku is another positive for the league. Aside from his obvious performance value – he is third top scorer in Serie A this season – Lukaku also brings some commercial pull. He is represented by the sports arm of Jay-Z’s commercial agency, Roc Nation, which specialises in finding players with both significant performance and commercial potential.

Inter have been particularly proactive at growing their social following over the last 12 months, having grown Facebook followers by around 70 per cent since last season and recently announced a new partnership with Twitter. More fans for Inter or Juve means more fans for Serie A, which ultimately bolsters rights values.

Recruitment is only one of the ways to access talent, and Serie A clubs have also fallen behind in their ability to develop players through their academy system – a fact highlighted by the insipid performance of the Italian National Team in recent times.

Our research into the transition of young players from youth to senior football has shown how important it is to grant young players opportunities early on in their career, and how poor Italian clubs are at doing it. While steps are being taken to remedy this – for example, Juventus have been granted a license to play a B team in Serie C – more could be done to help encourage the development of young, Italian players. Doing so would provide Serie A with reliable, cheap, and sustainable access to talent that would bolster the quality and efficiency of the league for the long-term.

Outside of talent, Serie A may also be ripe for competition restructure. Despite the title having been won by Juventus every season since 2011, the league is actually among the most balanced of the big five by some measures.

As of July 2020, the gap in our World Super League rating between the league’s best team (Juventus) and its sixth-best team (Roma) was the smallest of the big five European leagues, providing the ingredients for the most compelling title races in Europe over the coming years. Only LaLiga, meanwhile, has a smaller gap between the league’s best and worst team, which is mostly a function of the recent decline of its two biggest clubs.

Analysing what drives fans into stadia or into watching on TV can give leagues the confidence to try out more innovative formats that are specifically designed to attract more fans. Formats involving playoffs, for example, can create more points of interest throughout the league, reducing the number of dead rubbers and creating much-needed uncertainty in the title race.

While politically difficult to achieve, restructuring to make the competition more attractive to fans – and therefore to sponsors and broadcasters – ultimately serves the interests of the clubs through revenue growth.

The example given earlier of AFC Ajax struggling to live up to the tag of European football royalty was a principal motivation for bringing 21st Club in to review the format of the Dutch Eredivisie in 2018 – to grow broadcast revenues for the league and therefore the clubs. The success of format change in Belgium and Austria should give investors encouragement that a similar approach could help Serie A get closer to the Premier League over time.

Closing the gap

If you were standing in the Stadio Olimpico on May 22, 1996, you would have seen Juventus beat the then defending champions of the previous year, Ajax, 4-2 on penalties. You would have seen nine Italians selected to start by an Italian coach for Juventus and eight Dutchmen selected to start by a Dutch coach for Ajax.

At that point, it would have been hard to believe that 25 years later, Serie A, the dominant force in world football at the time, and Ajax, consecutive finalists and champions of the previous year, would be in the long shadow cast by the Premier League’s growth, both struggling to maintain competitiveness among Europe’s elite and to retain their best players in the face of financial inferiority. But that is precisely what has happened in the intervening years between that warm Rome night and today.

Serie A’s current position is hard to fathom given that Juventus’ triumph in 1996 was just one Italian success among many during those halcyon days. But those past heights should give encouragement to investors that the league may rise again. There remains enough in the Serie A brand, enough potential in their clubs and young players, and enough commercial and performance levers for a smart investor to pull to awaken this sleeping giant.

It is often said in sport that you learn more from defeat than victory – Serie A has had plenty of time to learn over the last twenty years. Perhaps any new investment will give the league fresh impetus to put those lessons into practice.

This article was originally posted in SportBusiness. You can find the original version here.